Working Class Hero - Morley's World #486

You won't find a scissor-door supercar living in Morley's shed, and here's why.

|

|

Dave Morley gives you the car advice you need – and maybe a bit about life as well.

|

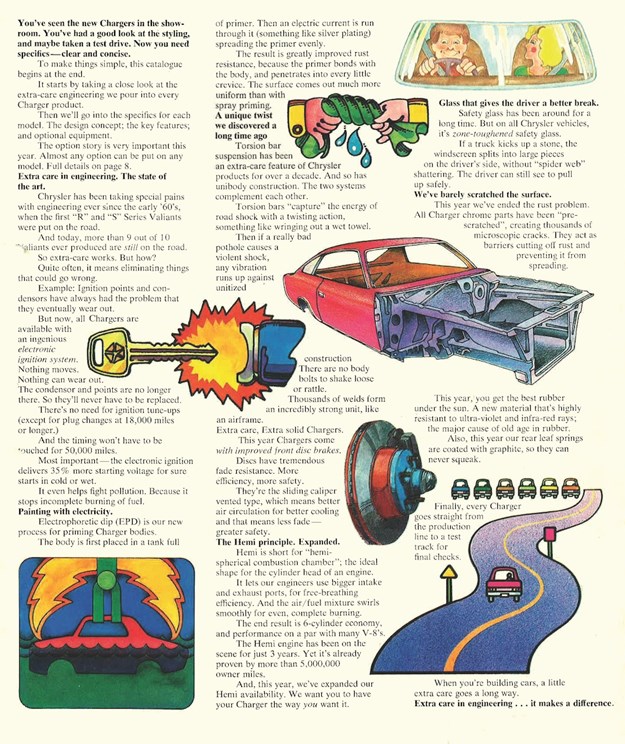

Having finally got the Charger properly on the road and running like a good ’un, I’m having a ball getting out in the thing on weekends and actually racking up a few kliks in the old mole.

And if there’s one thing that still amazes me, it’s the way the Val can draw a crowd faster than free money.

Seriously, I’ve made the point before, but you could park the Charger next to a brand-new McLaren and people would ignore ol’ Macca and make a beeline for the VH. But perhaps I shouldn’t have been so amazed at this phenomenon. Why?

Because, even though I’m too stupid to have figured it out earlier, I’m exactly the same. Oh sure, I’ll always be leaving drool marks on any Lambo Miura or Espada I spot lying around, and an F40 Ferrari will always get my attention.

But a modern supercar with a hybrid driveline, scissor doors and a price-tag with more zeros than a Pearl Harbour sky? Yeah, nah…

But why? Well, I started to think about that. Let’s look at the variables to see why people like us will gladly spend otherwise useful time ogling an ill-handling, mass-market sedan with stripes, while tripping flat on their face next to a supercar because they haven’t seen it sitting there.

So, is it inverse snobbery at work? I don’t think so. Even if we are talking blue-collar cars, I’ll still take the coupe version with the biggest engine rather than the Loser-Pack sedan with the bench seat and column-shift.

Which is not to say there aren’t folks out there who collect the base-model of a range of cars (g’day Byron) but that aint me.

|

| Nice, but not relatable. |

Okay, what about a lack of familiarity? Well, that’s a possibility, but not one that stacks up for me personally.

See, those decades I spent at Motor Magazine (RIP) allowed me to be snout-deep in a huge, ever-changing trough of supercars for a lot of the time, so I got to sample first-hand just how good a modern high-buck, high-performance car could be. And still I didn’t crave ownership of any of them.

Ah, you’re saying, but what about Porsches, Morley? You have a Jones for those. True, but to me, a Porsche is just a Stuttgart hot-rod anyway. And part of the appeal of a Porker has always been the way the products made so much from so little, with not a scissor door or V16 engine to be seen.

A 911 has always – for mine – represented two fingers to the established supercars. That’s my story, anyway, and I’m sticking to it.

So now let’s move on to price. Now, I’ve previously been quoted as saying the thing I find most attractive about a potential partner, is attainability. And it remains so.

But since when has the lack of the purchase price prevented any of us from being interested in something material? Exactly. A beer budget has never taken the fizz out of champagne tastes.

Is it a generational thing? No again, I reckon. Me and the Charger have been bailed up for a chat by people of all ages and by at least half of the 15 or so currently recognised genders.

So maybe it’s a working-class background, then. I certainly possess that. And I guess a big hairy bloke in work boots and a flanno, driving a raggedy-ass old Valiant is a lot more approachable than a hair-gel spiv in a Bugatti Veyron who is probably on his way to either kill a business rival or knock down an orphanage to build a casino.

Which brings it all down to relatability. You know, the stuff that Supercar racing seems (to me) to be lacking right now.

And maybe that’s not a bad metaphor for the whole thing: Supercar racing in this country should be about as exciting as anything is legally allowed to be. But, somehow, it’s not. To me, anyway.

|

| Hey Charger; old and battered and still making folk smile. |

Beyond the badge, there doesn’t seem to be any Camaro part numbers in a Camaro supercar, nor any Mustang in the Ford-badged equivalent.

Combine that with a driver cohort that lacks (with a couple of notable exceptions) the ability to produce a facial expression, and the fact you just can’t drive a modern supercar sideways and actually finish the race, so you wind up with a bunch or slot cars driven by robots. No relatability, in other words.

And I think maybe supercars are a bit like that, too. You’re in court before the end of second gear in most of them, and the only person who can believe how fast they are is a magistrate.

You can’t be lairy in them and, in fact, you can’t even drive normally in them, since they’ll snag a servo driveway on their front spoiler or crack a Kevlar side-skirt on your typical council speed-hump.

On the other hand, my old Charger has more than enough grunt to be entertaining, but can still be driven around normal roads without leaving its giblets on the driveway.

I can use all the gears (all four of ’em) and still be at liberty the next day. And, unlike the average supercar driver, with a 1973 Charger or any other working-class hero, you’ll never be lonely.

Local derby

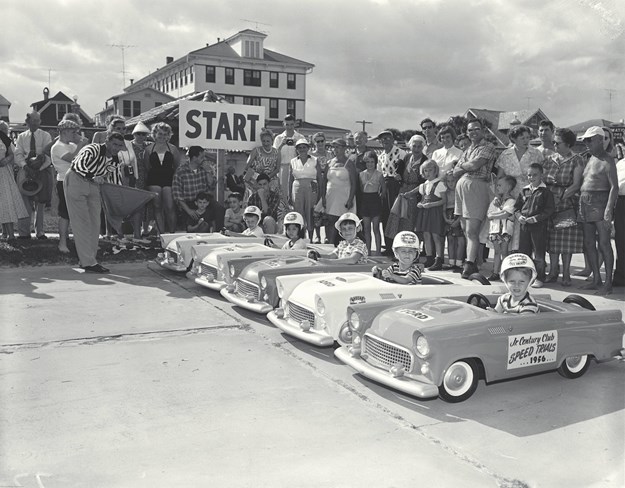

A couple of weekends ago, while searching for beer and a kebab in a part of town I don’t normally frequent, I stumbled across the local community billy-cart races.

Some communities have rubber duck races down the local creek, others go for the tried and true lamington drive (however that works).

But this joint had gone big and organised a fantastic event with about 50 billy-carts and their pilots ranging from bigger kids to tiny little tackers and even someone’s mum.

Like most billy-cart races I’ve seen, it was a pretty family affair with dad doing the race-team engineering, the various kids from the same clan taking turns to drive the ill-handling mutha down the hill, while trying to avoid the hay bales and mum cheering on from the sidelines, ready with encouragement and Betadine in roughly equal amounts.

And then dad lugging what’s left of the cart back up the hill for the next heat.

Yes, there were some good stacks. Nothing that anybody couldn’t limp away from, but I reckon Band-Aid’s share price might have got a boost in the days following.

Didn’t matter, because everybody seemed to be having an absolute whale of a time. And right next to the kebab van was a beer stand, set up by the local pub. A licensed billy-cart derby. Result. I love working-class suburbs. Obviously, I hung around for a while.

Probably the best thing about the day was that none of the little blighters had their heads buried in a mobile phone.

They were all busy, either trying to help dad reattach a rear axle that wanted no further part in proceedings, or attempting to straighten out the steering arms that had just had a deep and meaningful with a hay bale halfway through turn two.

Sometimes the between-races repairs worked okay, other times you’d see the same cart back out on the track with its front wheels toeing out, like a pole-dancer’s knees.

The level of design and engineering sophistication was hugely varied, too. One cart looked to have a cromoly-tube spaceframe with four huge racing bike wheels with skinny little tyres pumped up to 300psi.

|

| The PowerCar Co made juniors of production cars in the '50s and '60s in both petrol and electric. |

Some had crude, axle-on-a-pivot steering with a length of rope to haul it into turns, while others had proper rack-and-pinion set-ups, although it didn’t look as though anybody’s dad completely understood Ackermann-angle theory. Fair enough; I don’t either to be honest.

A couple of standout carts were one that looked like a scaled-down version of a dry-lake belly-tank racer. Lord knows what the body was from originally, but it looked great.

As did the Barbie-pink cart on steel roller bearings for wheels that rattled and screeched down the hill at a huge rate of knots while a tiny little girl (couldn’t have been more than four years old) in a Fisher Price My-First-Stack-Hat aimed it between the bales.

Naturally, not all the designs were as successful. Some had figured that three wheels represented less drag than four, but then made the mistake of laying the tripod out back-to-front.

As in, they put the two-wheeled end at the back and the single wheel at the front. This is 180 degrees out in terms of stability, as most members of the same family found out the hard way.

But this also got me thinking about some of my earliest engineering cock-ups. Which, not coincidentally, were also to do with billy-carts.

|

| Breeding our next Oscar Piastris. |

I learned very early on that the axles and wheels from a lawn mower were a great way to build a cart, but that attaching the axle to the wooden chassis with big nails bent over the axle was not a great way to proceed.

In the absence of a welder or even a proper drill, we soon developed an attachment method that involved locating the axle between and beneath strategically placed blocks of wood and nailing those to the chassis.

I also learned a lot about steering, mostly that a simple pivot for the front axle was easy to do, but resulted in steering that was far too quick and skittish.

Not to mention prone to jack-knifing and trapping your toes between the spine of the cart and the block of wood the front axle was mounted on.

In the absence of a better brain, however, I persisted with the single-pivot front end, but instead decided that the best way to prevent having my toes crushed was to move the axle farther forward, away from my perpetually bare feet (I didn’t own shoes till I was nine and we moved to the Snowy Mountains).

|

| It's just a turn to the left, then... |

This, however, meant that my feet could no longer help with the steering process, and the cart was now even more wilful than it had been thanks, to the rope steering that worked okay in tension, but was hopeless in compression.

Clearly, I needed to keep some pressure on the steering at all times to prevent it making too many of its own decisions. So, I rigged up a joystick kind of deal, from which ran a wire to the left-hand side of the front axle.

By pulling the stick back, I could get the cart to turn left. But what about right-handers? Ah, that was the job of the spring I half-inched from the screen door, on the side of the Morley shed.

With that fitted, bearing right became a process of letting the joystick come back to centre and then releasing pressure on it, allowing the spring to pull the axle around to starboard.

|

| Even GT attended this local cart race. |

Positives were the fact that, when parked, the steering went to full right lock preventing the cart from rolling away without me.

Downsides centred mainly around the same thing and what happened when the wire snapped and the cart assumed full right lock, but this time at anything up to 50 kays-an-hour.

Again, because I’m a dimwit, I persisted with this design right up until the point where mum put her foot down and declared it was either more Betadine or food and rent. But not both.

Fortunately, by then, I’d moved on to my mate’s old Yamaha 185 dirt bike. So everybody was safe again. Yeah, right.

Anyway, if your town or suburb doesn’t have an annual billy-cart derby, do something about it. Just make sure the hill is steep enough for some real speed and that your little derby is licensed. And I might even see you there.

Is it just me…

…Or is there something wrong with this picture?

|

| The right way or the wrong way? |

I’m not claiming to be a civil engineer or anything, but it occurs to me that this bus shelter has been installed bass-ackwards.

As in, it’s turned 180-degrees from where it should be so that the commuters unfortunate enough to actually shelter in it are facing the wrong way and will very possibly miss hailing their bus of choice.

Think about it: If you’re sitting in this particular shelter, you now have your back to the traffic (another poor choice, I would have thought in these days of rampant pedal-error).

This makes it difficult (if not impossible) to see your bus coming. Also, if you do manage to hail the bus, you then have to walk around the shelter to find the bus door and climb on board.

I’ve already mentioned this to a couple of people, one of whom assured me that this was now a thing in areas where the shelter is located on a narrow stretch of ground, close to the road.

The theory being that placing commuters’ dangling legs too close to the kerb is asking for trouble.

But isn’t sitting with your back close to passing trucks, busses and VR Commodores with P-plates a bit daft, too? If the strip of land is too narrow for a bus shelter, it’s too narrow which ever way you face the thing.

And the idea of being protected from 36 tonnes of B-Double by a sheet of glass (which will probably be on the ground in a million pieces next Sunday morning) doesn’t really work for me either. Or was some poor tradie just having a bad day when they installed the thing?

Any ideas?

From Unique Cars #486, Dec 2023

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)