Bygone Brands: Apollo

|

High-flying designs weren't enough to keep this heavenly body aloft

From the archives: Unique Cars #289, Aug 2008

For a country with a ravenous appetite for sports cars, North America’s track record as a source of specialised models has been abysmal.

During its early years, even the Chevrolet Corvette was on shaky ground for failing to deliver the attributes its target buyers found in their Jaguars and TR Triumphs.

There were promising designs from Briggs Cunningham and ‘Wacky’ Arnolt plus Carroll Shelby’s fearsome Cobras, but only the Corvette and Pontiac’s ill-fated Fiero managed to achieve volume production.

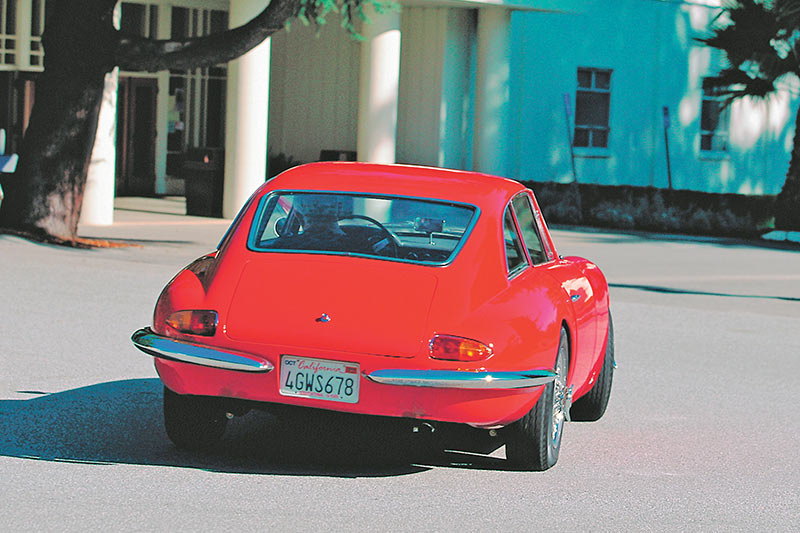

The early-1960s Apollo GT was another US project that offered huge potential but was doomed even before the first car turned a wheel. Convoluted logistics sent build costs higher than the car’s moon-orbiting namesake – and an engine that was underpowered and unreliable did the rest.

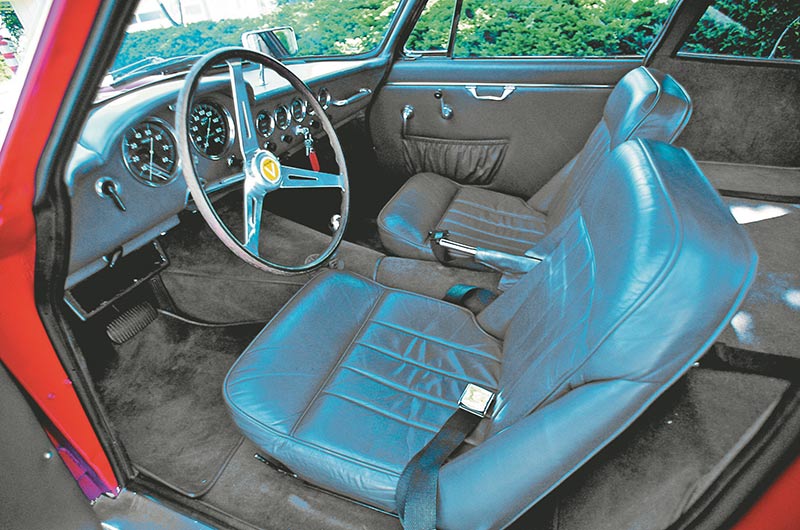

Creator Milt Brown was on the right path when he built a steel-tube chassis based on the remains of a fire-damaged Buick then contracted designer Ron Plescia, with whom Brown had collaborated to build America’s first Formula Junior racer, to design a body with overtones of Italy.

In partnership with Ned Davis, Brown established International Motor Cars and a factory in Oakland, California. The business immediately lived up to its somewhat pretentious name; fabricating chassis that were then shipped to Italy to be fitted with bodywork produced by a Hungarian-born Canadian.

Early in 1961, Brown had met Frank Reisner, a chemical engineer who left the paint industry to settle in Italy and establish Carrozzeria Intermeccanica. The fledgling business was already involved in racing car design and was building a high-performance microcar for Steyr-Puch in Austria, so Reisner was keen to break into the US market.

Early in 1962, the chassis and design drawings were shipped to Intermeccanica’s factory where a prototype was rapidly constructed and returned to the US. Reisner sought advice from former chief stylist at Bertone, Franco Scaglione, who suggested fitting rear side windows where Plescia’s design had none, enlarging the windscreen and shortening the car by more than 200mm.

With Americans at the time besotted by space exploration, the chosen name of ‘Apollo’ could well have been inspired by rocketships and talk of moon landings. In fact, it was actually suggested by Brown’s wife in honour of the Greek sun-god.

While most commentators attribute the Apollo concept to Milt Brown, the San Francisco Chronicle credited Plescia as its instigator. In a June 1962 article featuring the recently-arrived prototype, the Chronicle stated: "Plescia chose the lightweight Buick aluminium V8 as the heart of his design for the fast-back Apollo coupe."

Whichever of the duo decided on the 3.5-litre Buick motor – later acquired by Rover for its P6B and Range-Rover – they picked a dud.

With steel panels in lieu of aluminium, production Apollos weighed over 1200kg and struggled to get near the 212km/h top speed and 0-60mph (0-96km/h) time of 6.8 seconds that had been touted by the manufacturer. Magazine tests heaped praise on the car’s dynamics and build quality but bewailed the 3.5-litre model’s mediocre performance.

After producing 15 cars with the all-alloy engine, IMC relented and began offering the Apollo with optional 5.0-litre Buick V8s. The bigger engine developed an extra 45kW but weighed more, so improvements in performance were negligible.

During 1963, Scaglione penned and then produced a beautifully-proportioned Apollo convertible. This was the car that could have saved the brand, but dysfunctional sales management and cost increases blunted Apollo’s ability to compete in a tough market. In the end, only 11 of the open-top cars were built.

By late 1963, the 5000GT coupe was priced at over $7000 and battling to make progress against established brands. Jaguar’s E-Type was $1200 cheaper than an Apollo and 30km/h faster. Chevrolet’s 5.3-litre Sting Ray had appeared a year earlier and sold 21,500 cars in the time it took IMC to find owners for 30 Apollos.

Success would have come at a lesser cost, had the plan hatched by a Los Angeles Buick dealer been allowed to succeed. Upon seeing the prototype, dealer Phil Hall ordered 50 cars, with the intention of rebadging them as Buicks. However, Buick management got wind of the deal and jumped on it from a considerable height.

To remain afloat, IMC sold off a few body/chassis kits for home completion. By late 1964 it was all over for IMC – although not for the resilient Apollo.

Stuck with a factory full of part-finished product, Reisner and Brown searched for a means of liquidating their problems. Salvation came in the shape of Dallas-based Vanguard Air Conditioning, which bought Reisner’s stock of empty shells with the intention of marketing them under the name ‘Vetta Ventura’.

Vanguard’s attempts at shifting an overpriced, quasi-Italian coupe were even less successful than IMC’s. Of the 16 coupes and three convertibles it bought, Vanguard finished fewer than half before selling some to a nearby car dealer and the rest to private buyers. A couple reportedly were scrapped, but they could have been completed cars that were written off in crashes.

A new business established in 1964 by Robert Stevens revived the project and contributed a further 24 Apollos to a population that is generally acknowledged to total just 88 two-seat cars plus a solitary prototype 2+2.

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)