Feature: Lancia Rallying

Incredible twin-charged Lancia Delta S4

Incredible twin-charged Lancia Delta S4

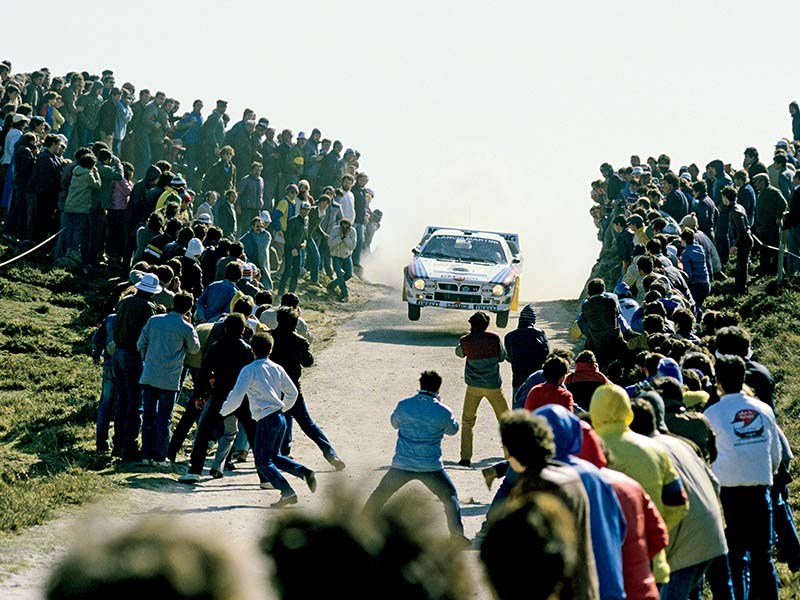

Lancia rally

Lancia rally

Lancia rally

Lancia rally

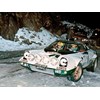

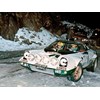

Henri Toivonen threads the needle on the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally

Henri Toivonen threads the needle on the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally

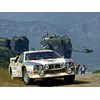

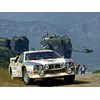

Sublime 037 slides past the famous Meteora monastery during the 1982 Acropolis Rally in Greece

Sublime 037 slides past the famous Meteora monastery during the 1982 Acropolis Rally in Greece

Juha Kankkunen resorts to desperate tactics during the 1990 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland, operating the throttle manually after the cable broke

Juha Kankkunen resorts to desperate tactics during the 1990 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland, operating the throttle manually after the cable broke

Lancia's rally weapons proved not only devastatingly fast but incredibly tough

Lancia's rally weapons proved not only devastatingly fast but incredibly tough

Martini Racing stripes on the humble service vans

Martini Racing stripes on the humble service vans

Italian Miki Biasion survived the Group B era to win back-to-back championships for Lancia in 1988 and '89

Italian Miki Biasion survived the Group B era to win back-to-back championships for Lancia in 1988 and '89

Two mechanics fixing Simo Lampinen's Lancia Fulvia in the Morocco heat

Two mechanics fixing Simo Lampinen's Lancia Fulvia in the Morocco heat

Undressed Stratos sits in front of Lancia Beta Group 5

Undressed Stratos sits in front of Lancia Beta Group 5

Markku Alen confers with fellow Finn and 1986 teammate, Henri Toivonen

Markku Alen confers with fellow Finn and 1986 teammate, Henri Toivonen

Didier Auriol had an enormous crash after landing badly from a jump during the 1989 San Remo Rally

Didier Auriol had an enormous crash after landing badly from a jump during the 1989 San Remo Rally

1974 Rideau Lakes Rally in Canada

1974 Rideau Lakes Rally in Canada

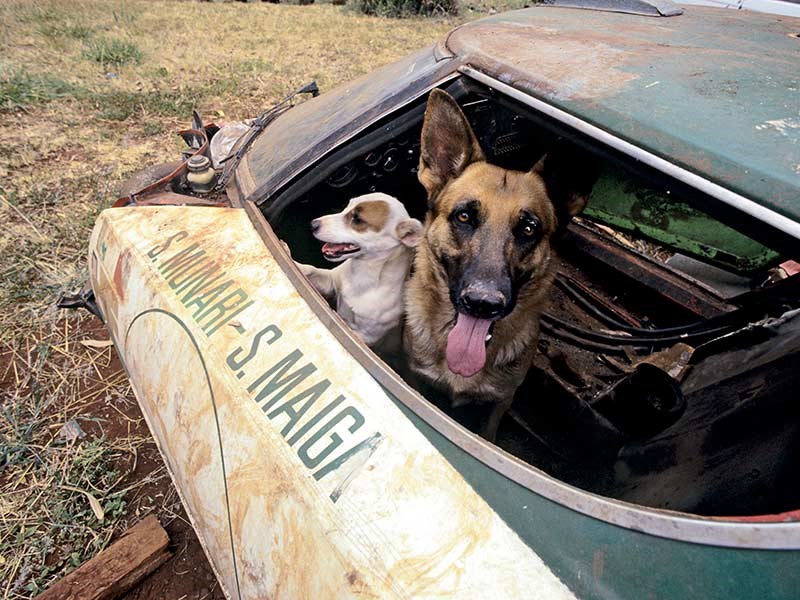

A Works Stratos, abandoned in Kenya following the Safari Rally forms the world's most expensive dog kennel

A Works Stratos, abandoned in Kenya following the Safari Rally forms the world's most expensive dog kennel

Auriol sprays the champagne at the 1990 Monte Carlo Rally, the first of his three wins that year

Auriol sprays the champagne at the 1990 Monte Carlo Rally, the first of his three wins that year

|

|

Incredible twin-charged Lancia Delta S4

|

|

|

Lancia rally

|

|

|

Lancia rally

|

|

|

Henri Toivonen threads the needle on the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally

|

|

|

Sublime 037 slides past the famous Meteora monastery during the 1982 Acropolis Rally in Greece

|

|

|

Juha Kankkunen resorts to desperate tactics during the 1990 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland, operating the throttle manually after the cable broke

|

|

|

Lancia's rally weapons proved not only devastatingly fast but incredibly tough

|

|

|

Martini Racing stripes on the humble service vans

|

|

|

Italian Miki Biasion survived the Group B era to win back-to-back championships for Lancia in 1988 and '89

|

|

|

Two mechanics fixing Simo Lampinen's Lancia Fulvia in the Morocco heat

|

|

|

Undressed Stratos sits in front of Lancia Beta Group 5

|

|

|

Markku Alen confers with fellow Finn and 1986 teammate, Henri Toivonen

|

|

|

Didier Auriol had an enormous crash after landing badly from a jump during the 1989 San Remo Rally

|

|

|

1974 Rideau Lakes Rally in Canada

|

|

|

A Works Stratos, abandoned in Kenya following the Safari Rally forms the world's most expensive dog kennel

|

|

|

Auriol sprays the champagne at the 1990 Monte Carlo Rally, the first of his three wins that year

|

For two glorious decades the Italians ruled the world's toughest motorsport discipline with military precision...

|

|

Lancia Delta Integrale

|

Lancia Rallying

DELTA FORCE

Pop quiz: which manufacturer has won the most World Rally Championships? You might guess Ford, given the Escort virtually owned the sport in the mid-to-late ’70s; or perhaps Subaru or Mitsubishi, their turbocharged all-wheel drive rockets – driven in spectacular fashion by Colin McRae and Tommi Mäkinen – lifting the WRC’s popularity to F1-rivalling levels in the late-’90s.

But no, neither the hardy blue-collar heroes from the UK nor the rugged Japanese offerings have tamed the world’s toughest motorsport as well as the cars from a small, quirky Italian manufacturer called Lancia. Between 1972 and 1993, the Turin firm won one International Championship for Manufacturers (as the manufacturers’ title was known prior to 1973) and 10 WRC titles.

Lancia made its name as a maker of incredibly innovative (and often quite beautiful) vehicles. It can lay claim to the first production version of the V4 and V6 engine, five-speed gearbox, monocoque bodyshell and more. But innovation is rarely rewarded in the rough-and-tumble world of rallying, especially in the sport’s early years, when endurance and reliability were more important factors than out-and-out speed.

Victory in the 1954 Monte Carlo Rally, legendary Grand Prix driver Louis Chiron driving an Aurelia GT, provided a hint of what was to come, but it wasn’t until the small, lightweight, front-drive Fulvia Coupe was launched in 1965 that Lancias began regularly appearing on special stages. Initially outgunned by the more powerful Porsche 911 and Alpine-Renault A110, the arrival of the Rallye HF 1.6 model turned the Fulvia into an outright contender.

Conceived with a competition career in mind, the HF 1.6 was factory fitted with wheel-arch flares, extra lights and bigger alloy wheels. The most important change, though, came under the bonnet, a 1584cc DOHC V4 that offered up to 118kW in race tune and finally gave the Fulvia the grunt to match its handling. In 1972, victories in Monte Carlo, Morocco and San Remo delivered Lancia the International Championship for Manufacturers.

Come 1973, the inaugural World Rally Championship, the superior speed and resources of the Alpine-Renault team overwhelmed the Italians, but hidden away in the French and Italian national championships, the bugs were being ironed out of Turin’s secret weapon, a car that would revolutionise the world of rallying.

The Stratos was like a supermodel that had enrolled in the SAS; it may have looked fit for the streets of Monaco but beneath that exotic bodywork was a car purpose-built to get from point-A to point-B as fast as possible, regardless of the surface or terrain. The body was a sheet-steel monocoque while the 2.4-litre Ferrari V6 and five-speed gearbox were housed in a huge rear subframe for both strength and ease of servicing.

Weight was just 890kg, while power was 300bhp in race trim. Spectators would trudge for hours through mud and snow for a glimpse of the Stratos in action, but the true reward was listening to the harsh bark of the unsilenced Ferrari V6, able to be heard for miles on a still night.

Victories in Italy, Canada and France secured Lancia’s first WRC title in 1974, with two of those wins (Italy and Canada) coming courtesy of Italian driver Sandro Munari. Having made his name by driving Fulvias at indecent speeds, Munari became rallying’s benchmark driver and was akin to a god in his home country. Fans would kiss the ground after he had driven past and Lancia spared no expense looking after its star’s every whim, including assigning him a personal doctor. Munari was incredibly fast, but his performances varied wildly according to his mood. In an attempt to hedge against Munari’s bad days, Lancia signed Swede Bjorn Waldegard (who sadly recently passed away) for 1975, the move immediately paying dividends with Munari winning in Monte Carlo and Waldegard in Sweden.

Another win for Waldegard in San Remo made Lancia’s second successive title a formality, particularly as the only real competition came in the form of Fiat’s 124 Spyder. With Fiat understandably refusing to spend a fortune to compete with itself, and no other manufacturer prepared to commit the resources necessary to challenge the Italians, Lancia’s drivers turned their attentions to each other.

A 1-2-3 in Monte Carlo should’ve been the perfect start to season 1976, but beneath the surface, cracks were beginning to appear. Waldegard had been ordered not to challenge Munari for first place, team management eager not to let the Swede’s speed rattle their favourite son. In San Remo later in the season, it appeared Waldegard would get his reward, with Munari ordered to hold station in second. But Lancia team manager, Cesare Fiorio, had other ideas. On the start line of the final stage, he held Waldegard for four seconds – exactly the length of his advantage over Munari – to ensure his charges had a one-stage shootout for the win. Despite winning the rally – fittingly by four seconds – Waldegard was furious and immediately signed for Ford. It appeared nothing could stop the Stratos. Nothing, that is, except internal politics. Seeing little return on its apparently bottomless investment in Lancia’s rallying activities (after all, only 492 road-going Stratos were built), Fiat pulled the pin on its exotic supercar and made the humble 131 sedan its rallying pin-up.

The move worked, Fiat capturing the 1977, ’78 and ’80 manufacturer titles, but as late as 1981 privately-entered Stratos were still winning World Championship events, a new generation of drivers being enthralled and intimidated in equal measure. Its short wheelbase and mid-engined layout challenged even the world’s best, as Walter Röhrl explained: "The Stratos spun when you even thought about braking hard. You were simply not allowed to make mistakes."

With Lancia out of action on a championship level, Fiat and Ford waged a furious battle for rallying supremacy, before Audi turned the whole game on its head with the introduction of all-wheel drive. This coincided with the switch from the production-based Group 4 regulations to the much more liberal Group B, which would instigate a technological arms race that would engulf the sport for the next five years.

Group B opened the door for Lancia to rejoin rallying’s ranks in late-1982. Unusually for a company that prided itself on innovation, the Italians ignored the promise of all-wheel drive, reasoning that the system’s weight and complexity would outweigh any traction advantage. Instead, the Lancia engineers, led by the late Giorgio Pianta, created the 037 – the ultimate rear-drive rally car.

A steel spaceframe and and fibreglass panels kept weight to just 960kg, while power from the mid-mounted 2.0-litre supercharged four was set at 305bhp, with a huge torque spread and instant response; a key advantage when lined up against the turbocharged opposition.

Once Lancia’s drivers squeezed into it – both Markku Alen and Walter Röhrl easily topped six feet tall – they never wanted to get out. "The 037 was precise and neutral," said Rohrl. "It could be controlled almost entirely with the throttle. It was much smoother than the Stratos, but equally nimble."

Nonetheless, Lancia soon realised it had made a significant technical error, the incredible rate of development allowed by the new regulations making all-wheel drive a necessity. Incredibly, though, Audi squandered its significant advantage with disastrous reliability and despite Hannu Mikkola becoming the first WRC driver’s champion with an all-wheel drive car in 1983, Lancia captured another manufacturers’ title.

This was largely thanks to the incredible abilities of Alen and Röhrl; Röhrl could even have won the driver’s title, but the stubborn Bavarian refused to drive in Finland and preferred a holiday with his wife to competing in Argentina. Team manager Fiorio also played a significant role with his ability to squeeze the rule book until it cried for mercy.

Take the 1983 Monte Carlo Rally, for example. While the majority of the route was dry, sporadic sections of snow put the rear-drive Lancias at a significant disadvantage. Fiorio’s solution? Order 300 tons of salt from Italy and have it spread over the stages, melting the snow and enabling the use of slicks. On another stage Fiorio installed a service crew mid-stage, allowing the drivers to cover the snowy sections on studded tyres yet swap to slicks for the remaining tarmac. Röhrl won by almost seven minutes from Alen.

It quickly became clear the following year that Lancia needed a new challenger, and fast. A one-two in Corsica was its only success in a year dominated first by the ever more powerful Audi Quattro and, later, Peugeot’s new mid-engined rocketship, the 205 T16. But the complexity of these new Group B machines meant development was not the work of a moment, and Lancia’s new weapon didn’t debut until the last round of 1985.

In the meantime, Peugeot had established itself as the dominant force in the WRC, winning both titles by a mile. There were growing whispers, however, that this spectacular new breed of rally machines might be a step too far. Former world champion Ari Vatanen’s life hung in the balance following a high-speed crash in Argentina and Attilio Bettega lost his life in Corsica behind the wheel of a 037. Prior to his death, Bettega confided that he felt rallying was close to its limit, that pushing Group B cars to the limit may soon be beyond human endeavour.

There’s a certain irony, then, that Lancia’s new Delta S4 upped the ante even further. Exotic materials kept weight to a scant 900kg, yet thanks to a supercharger and turbocharger, its tiny 1.8-litre four-cylinder developed 480bhp on debut and only increased from there. In the hands of wild Finnish young gun, Henri Toivonen, the S4 won on debut and was often just a blur across the landscape.

The 1986 title seemed a formality, but sadly, more tragedy quickly followed. Crowd control was becoming a major problem and three spectators were killed and dozens injured when a car left the road in Portugal. All the top drivers pulled out immediately in protest, but the real shock came two events later, again in Corsica, when Toivonen crashed while leading, killing he and co-driver Sergio Cresta almost instantly.

The car burst into flames on impact and burned with such ferocity that by the time rescue crews arrived, there was nothing but a vague outline of a charred rollcage. Three weeks later, the sport’s governing body banned Group B cars for the 1987 season and beyond. Audi and Ford pulled out immediately, leaving Peugeot and Lancia to stage a furious battle for the title.

The championship would not be decided on the stages, however, but by petty national politics in a courtroom. At the San Remo Rally, (Italian) scrutineers had deemed the Peugeot’s side skirts illegal and disqualified them. Lancia’s subsequent 1-2-3 helped it capture both the drivers’ and manufacturers’ titles, yet following an appeal held in Paris, Peugeot’s home ground, the results were annulled and the 1986 titles went to the French. It was a farcical way to end rallying’s most exciting era.

The production-based Group A regulations became the sport’s premier category going forwards. Still high on the thrills provided by the fire-breathing Group B machinery, the impotence of these new cars led many drivers to question whether they wanted to continue. Lancia’s Markku Alen summed up the thoughts of most: "It felt like the world had ended. Our S4 was developing about 700hp by the end; the Group A Delta had around 230. It just felt like driving a road car and I was so frustrated by everything I really wondered what the point was in continuing."

Nevertheless, it was Lancia who was best placed for success under the new regulations, its ageing Delta HF 4WD a natural fit for Group A, as proved by a 1-2 at the season-opening Monte Carlo Rally. Once again the cunning of team manager Cesare Fiorio played a significant role.

Rivals knew Lancia hadn’t built anywhere near the 5000 cars required for homologation, but with the sport in such a precarious state Audi refused to protest, despite the Deltas appearing in standard form for scrutineering yet sporting a number of obvious modifications once they hit the stages. With no real competition, Lancia utterly dominated the 1987 season, winning nine of 13 rounds and doubling the points of its nearest challenger (Audi).

This set the tone for the next half-decade. Lancia introduced the vastly improved Delta Integrale for the 1988 season, a car that would deliver five straight manufacturers’ titles and three drivers’ titles, the Toyota Celica GT-Four of Carlos Sainz the only fly in the ointment. Secret to the Integrale’s incredible success was the relentless pace of development, Lancia somehow managing to find more power, more suspension travel and wheel width and greater chassis balance with each successive season.

But the greater the pride, the harsher the fall and Lancia’s tumble from grace was swift and brutal. From eight wins and its 10th manufacturers’ title in 1992, the best it could muster in 1993 was a pair of second places. Rallying’s axis of power had shifted east, as Toyota, Subaru and Mitsubishi readied themselves to take the reins of dominance for the next decade. It was a sobering reminder that top-level motorsport gives little regard to history or provenance.

Lancia now exists as a shadow of its former self. Its current range is a collection of Fiat-based eyesores and rebadged Chryslers, a far cry from its pioneering early creations. Thankfully, as the years pass, the cars that serve as reminders of Lancia’s glory years are becoming sought-after classics. More importantly, though, dedicated groups of enthusiasts are keeping these cars out where they belong, on the rally stages.

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)