Shelby AC Cobra Review

|

Carroll Shelby's inspired blending of Detroit muscle with British handling still charms

AC Cobra

It would be nice to think that Carroll Shelby was settling over a beer one day and started sketching his dream car on the back of a coaster, pocketed the results and started organizing it. As with many things in life, the Cobra in fact happened more by accident than design.

The germination for the product began when Shelby – who had impeccable industry connections through Europe thanks to his illustrious race career – heard that the troubled British firm, AC, had lost its engine supply and was hunting around for a new powerplant.

Up to then, its Ace sports car had used a few powerplants, with the 120hp Bristol two-litre straight six being the most successful. Talks had been held with Jaguar, but had gone nowhere.

Meanwhile Shelby, after some hesitation, wrote to Charles Hurlock, brother of AC owner William, with the idea of mating the chassis to an American V8 – at that stage no particular motor was in the frame. Shelby soon after (October 1961) approached Ford on learning the company was producing a 221ci small-block V8.

Both AC and Ford saw merit in the idea and work was begun on a prototypre using the 221 engine. While retaining the general lines of the Ace, the Cobra turned out to be the on-steroids version. Under the skin, the changes were massive, with a far stronger chassis, designed to run with a Borg-Warner four-speed transmission and a Salisbury diff, complete with inboard brakes. The brakes were later moved outboard to reduce costs. A couple of test drives in the UK convinced everyone they were heading in the right direction, and the project soon moved across the Atlantic.

Roll forward to February 1962 and Shelby takes delivery of the prototype car – sans engine – which had been air-freighted across from England. Local magazine Motor Racing quizzed Shelby on what he was up to. The objectives, they announced were to make some money; and, more importantly, to knock off the Corvettes and E-Types. By ‘knock off’ Carroll was happily predicting triumph over the main contenders on local race tracks. As history shows, his prediction was all too accurate. Competitors knew their race was effectively over when the Shelby transporter, with three Cobras on board, turned up in the pits.

Though the original prototype was built around the 221 engine in California at Shelby’s new Venice facility (opened in March 1962), it scored the 260 cubic inch V8 – essentially a Fairlane powerplant.

The very first show car (with ID CSX2000) was sent to the New York Auto Show in April of that year and caused a sensation. Initially presented in pearlescent yellow, it was painted different colours for different magazine road tests, to give the impression of the existence of a fleet of cars. The car is still in existence and, last time we saw it in 2012, it was blue. Given it’s worth in the vicinity of US$5 million (about three times a ‘normal’ Cobra) you probably wouldn’t be overly concerned about the colour!

The first 75 cars ran with the 260-horse, 260-cube engine and, weighing a shade under 1000kg, they almost literally flew. Zero to 60mph was independently tested at a stunning 4.1sec, while the car could do a 12.9sec standing quarter. Top speed was 152mph (243km/h). They’re numbers that would look respectable in a modern performance car. That lot would set you back a cool US$6000 – or about double the price of a decent family car. A race version was estimated at around $7200.

To quote a 1962 road test from Sports Car Graphics magazine, "Perhaps one of the most outstanding attributes of the Cobra, aside from the combination of docility and brutal performance, is the fact that for its type it is a very live-able car." So this was no quickie workshop special – it was in fact regarded as a well-sorted piece of machinery with (for its day) astoundingly high limits of adhesion.

The final 51 Mk1 cars were powered by Ford’s new 289 Windsor, which went on to be the powerplant of choice for Shelby’s GT350 Mustang.

Numerous changes – some subtle, some outrageous – were made to the car over its three generations of production, with chassis production primarily done at AC in Britain, with finishing work in California. An example of the former was the adoption of rack and pinion steering for the MkII cars, which actually involved some major re-engineering.

As for outrageous, it doesn’t get any more ridiculous than stuffing a 427 powerplant into this shoe-sized car. Designed with assistance from Ford in Detroit, these MkII units incorporated coil springs all round and a beefed-up chassis, boasting 425 horses and a 164mph (262km/h) top speed.

Despite the headline numbers, the 427s were not a financial success and struggled in the showroom. In fact, many chassis were subsequently fitted with the cheaper 428 powerplant (smaller bore and longer stroke, with milder performance). The final 31 unsold examples were dressed up as special-edition S/C (semi-competition) cars and have since become hot property among collectors.

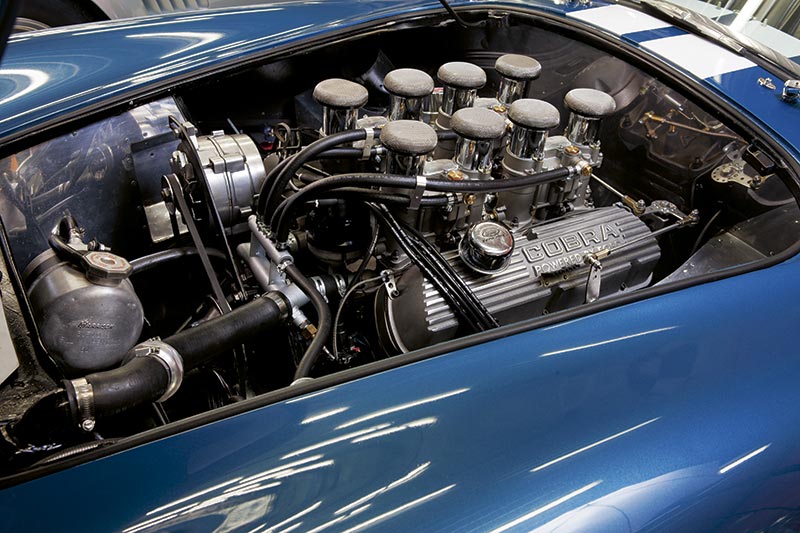

So are they all they’re cracked up to be? A few years ago we threw John Bowe into a locally-owned MkII car (shown here), fitted with a set of Weber downdraught carburetors, to get some expert feedback. "These are very basic cars – they haven’t got any creature comforts," he commented. "Like all cars of the period, it’s got gauges everywhere with no thought to where they are placed and they’re probably not that accurate.

"In true American fashion it starts nicely and, with a pipe out each side, it sounds great. When you give it to it, I reckon you can hear it four suburbs away! You’ve got eight carby throats sucking and the exhaust is going off, and you can imagine yourself at Sebring in 1966.

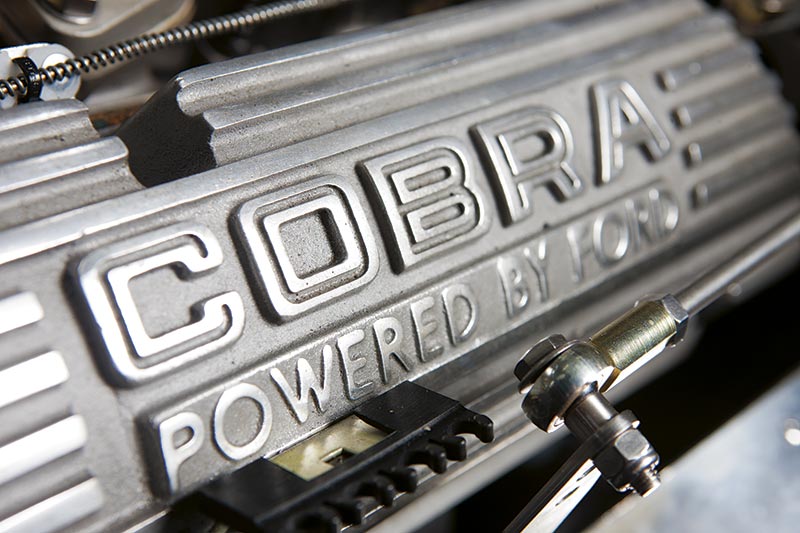

I think the Ford small block redefined the American V8 engine. It was compact, light, and ended up in so many great cars. ‘Powered by Ford’ really meant something in the 1960s.

"The power to weight ratio is very good and it wheelspins and snakes around.

"You turn it into a second-gear corner and it has quite a nice feel. Then it gets a bit of understeer and, when you bring the throttle into play, it starts to wiggle its arse. It wants to break traction really easy – not into full-blooded slide, but the chassis and LSD are trying to cope with the traction loss.

"The brakes are quite reassuring but I’m sure if you used them too hard for too long you’d run out of stopping power, because the discs are very small.

However, he also commented on how docile it could be. "It’s light and has a flexible engine – you could drive it every day," he added. Sounds good doesn’t it"? If only our forebears had been smart enough to buy a couple and put them away for a while…

KNOW YOUR COBRAS

MKI

1962-63, 260 or 289 engine

126 produced

MKII

1963-1965, 289 engine

Approx 528 produced

MKIII

1965-67, 289 or 427 engine

Approx 327 produced, including AC289 variants

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)