Plymouth Road Runner: Classic

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

|

|

Plymouth Roadrunner

|

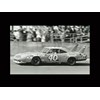

With Chrysler Corp's thumping 426 Hemi under its bonnet, Wile E. Coyote had no chance of catching this Road Runner

|

|

Classic: Plymouth Roadrunner

|

Plymouth Road Runner

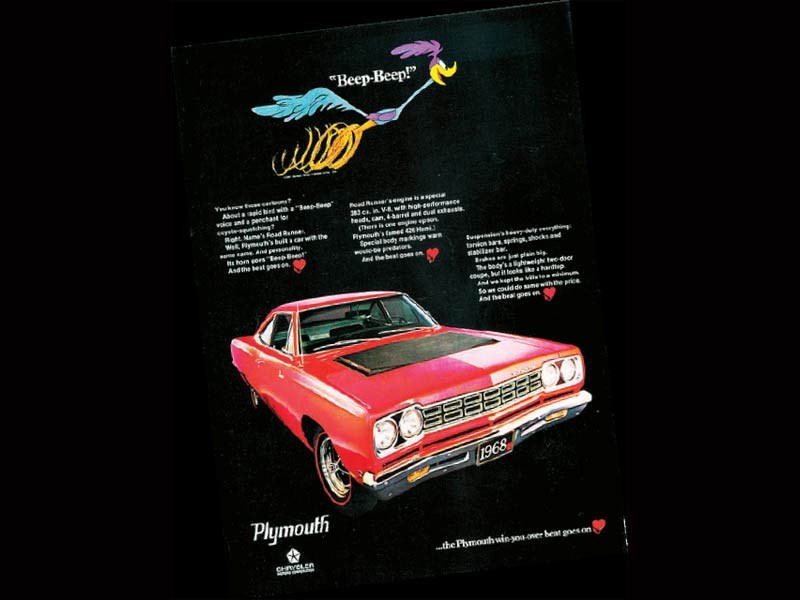

BEEP! BEEP!

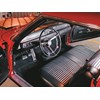

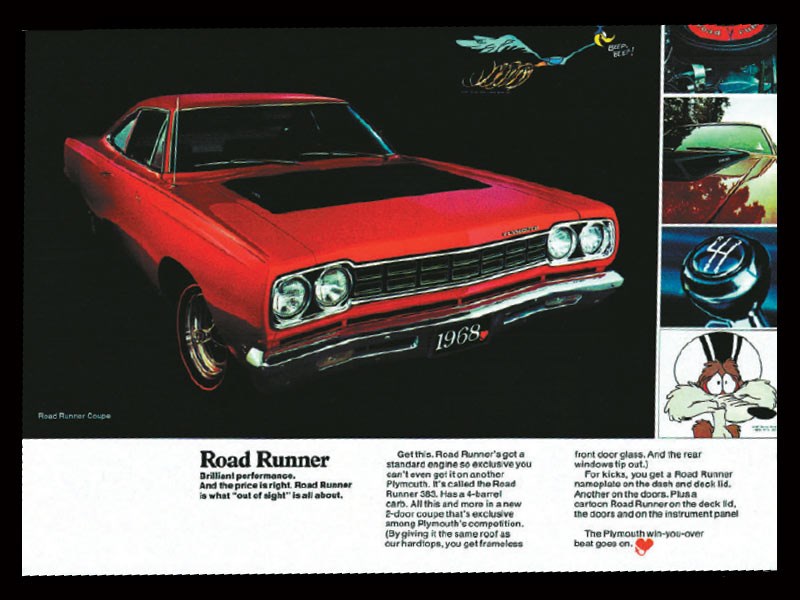

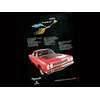

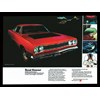

Road Runner – has there ever been a more appropriate name for a performance car? And what a recipe for excitement. Take one handsome, if rather unassuming US ‘mid-sizer’, make sure it’s a two-door, strip out all the kit, and load it with performance weaponry.

Make no mistake, on the quarter-mile battlefield, even a ‘standard’ 383ci 1968-70 Plymouth Road Runner was fighting on the front lines. When US mag Motor Trend tested a Road Runner fitted with the optional 426 Hemi, it blasted from 0-60mph (0-97km/h) in just 5.3sec and demolished the quarter mile in 13.55sec!

Hemi-equipped Road Runners were thin on the ground, though. Just 1019 were sold in ’68 – 576 manuals and 443 autos. Why so few? The fact that the Hemi was an eye-watering $714 option on a car with a base price of $2896 may have had something to do with it. Add the necessary Torque-Flite auto ($38.95) and Sure-Grip limited-slip diff ($42.35) and the Road Runner no longer seemed like such a performance bargain.

Most buyers ‘made do’ with the 383ci ‘Road Runner’ V8 that was bespoke to this new Plymouth and developed 335hp/425 ft.lb (250kW/576Nm) to the 426 Hemi’s 425hp/490ft.lb (317kW/664Nm). It may have lacked the Hemi’s towering performance, but the 383 also lacked its driveability and tuning hassles.

In the mid-’60s, Plymouth was suffering an identity crisis. Its average buyer was eligible for a pension and its cars were as popular with the youth market as lawn bowls. The groovy kids were buying Pontiac GTOs hand-over-fist. Desperate to appeal to a younger audience, Bob Anderson, vice-President of Chrysler-Plymouth, asked legendary US motoring writer Brock Yates, "What do I have to do to get the kids’ attention?" Yates’ answer was simple: take a car, strip it of everything bar the essentials and fit the biggest engine you’ve got.

Armed with this advice, Plymouth set a number of key targets. Using Chrysler’s B-body platform that underpinned everything from the Dodge Charger to the Plymouth Belvedere, the car had to do 0-60mph in less than seven seconds and 0-400m in under 15, straight off the showroom floor. It had to have highperformance suspension, brakes and ABOVE Mid-size Plymouths used 116-inch version of Chrysler’s ‘B’ platform. Contemporary Dodges added an extra inch transmission, and had to sell for under $3000. No-one had built a bare-bones muscle car before, though, and it was a giant leap into the dark for the notoriously conservative Chrysler Corporation.

Adding performance was no problem. Chrysler had 51 percent of the police car market, allowing hi-po bits to be pilfered from its police division. But Road Runner was conceived after the ’68 model- year Plymouths had been finalised. It went from concept to production in just two months. To quicken the process, the task of coming up with a name was given to advertising agency Young & Rubicam. Y & R requested a meeting with Jack Smith, manager of Plymouth’s mid-size product planning.

Prior to that meeting, however, Smith’s assistant, Gordon Cherry, said he had found the perfect name that embodied all the characteristics of Plymouth’s bold new car. "Do you ever watch Saturday morning cartoons?" asked Cherry. Smith duly did his research and loved the idea.

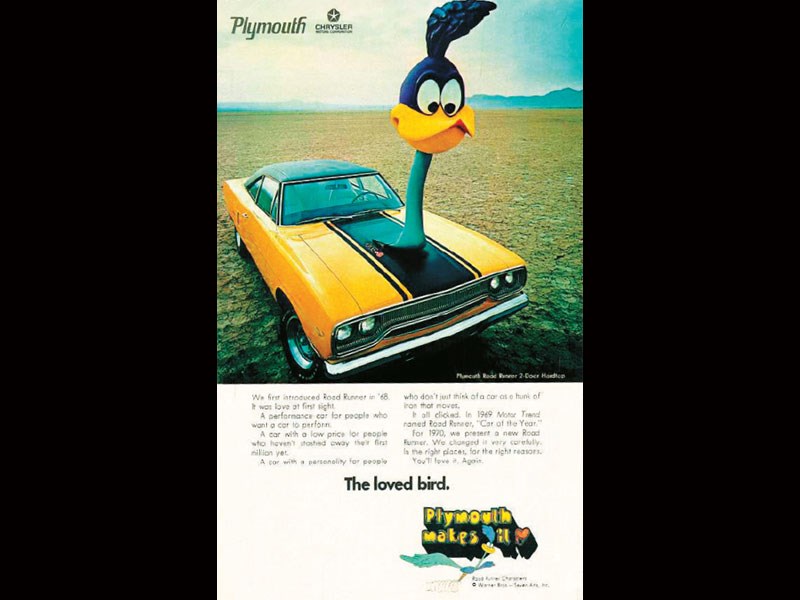

The name that Y & R had chosen was Lamancha, but upon hearing Smith and Cherry’s suggestion, immediately recognised the marketing opportunities. Smith remembers that the agency’s art guy was so excited that he began physically shaking.

Smith contacted the American Motoring Association, which had a gentleman’s agreement that if you were the first to register a name, the name was yours. Road Runner was available and subsequently assigned to Plymouth. Next came negotiations with Warner Bros., whose long-running cartoon provided the inspiration for the name.

The film studio’s lawyers were preparing to play hardball, but the wind was taken out of their sails when Smith reminded them that, given the roadrunner was an actual creature (a small bird native to south-western US states and northern Mexico), the only point of contention was whether Plymouth could use the cartoon character in advertising. Recognising the potential brand synergy, Warner Bros. agreed to the proposal for an annual sum of $50,000.

Plymouth leveraged that permission at every opportunity. Road Runner (which, incidentally, looks nothing like a real roadrunner) featured heavily in period advertisements, and the cartoon bird’s nemesis, a worried-looking Wile E. Coyote, appears in the ’68 brochure. But Plymouth still had to "get the kids’ attention", so Smith set about using the cartoon character’s image to inject some personality into the car. Smith’s idea was to use Road Runner’s famous catch-cry "Beep! Beep!" as the new model’s horn sound.

A tape was sent to Plymouth’s three horn suppliers, yet only one had a match. The installation of this unique feature accounted for half the tooling costs of the Road Runner! Despite the need to keep the purchase price as low as possible, Smith was determined for the car to stand out from the norm.

It was at this point that bureaucracy threatened to derail the whole project, with that horn providing the first hurdle. Plymouth required that each horn pass an engineering cycling test. With no time to complete the test, Smith wrote a letter assuming full responsibility for the horn if the engineering department released it immediately, despite having no authority to do so.

Hurdle number one cleared. Creating a bespoke engine was hurdle number two. Smith’s racing friends – as product planner, Smith was the driving force behind the project – suggested the hotter camshaft, valve gear, head castings and exhaust manifolds from the GTX’s 440ci ‘Super Commando’ V8.

While the installation of these parts was relatively easy, Plymouth’s engine plant was already straining under the pressure of assembling so many different variants. Adding yet another was not going to be popular, but an impassioned pitch by Smith to chief engineer, Bob Steere, gave the new engine the green light.

Dean Engle, chief engineer of Powerplant engineering, was less enthusiastic, claiming the changes wouldn’t have the desired effect. He built two prototypes with the Road Runner engine, and both times incorrect parts were installed that compromised the driveability of the car. An unfortunate coincidence or an attempt to put Smith off the idea of a special engine? The changes were eventually made to all 383ci engines, so draw your own conclusions from that.

The exceptions to this were Road Runners fitted with air-conditioning, which received the regular 330hp/400ft. lb (246kW/542Nm) Super Commando 383 V8, as the hotter cam specs of the Road Runner engine wouldn’t supply enough vacuum to run the air-con.

The car looked set for success until Dick McAdam, styling director for Chrysler-Plymouth, threw a spanner in the works by saying "Nobody, but nobody, will ever put a cartoon bird on one of my cars." Doing some quick thinking, Smith offered to put the Road Runner decals in the glovebox and let the customer decide whether to apply it.

He then went one step further, ordering assistants to covertly apply the decals prior to a dealer conference displaying Plymouth’s new models, attended by then-president Virgil Boyd. The positive response sealed the deal – the Road Runner would enter production as Smith intended.

The hard work paid off as Plymouth’s new Road Runner became a smash hit. The initial sales forecast for 1968 was 2000 units, whereas the actual total was 44,599. It could’ve been higher but since purchasing orders had been created on the basis of that initial forecast, Plymouth almost immediately ran into supply problems.

In 1969, a convertible joined the Road Runner line-up, and the 390hp/490ft. lb (291kW/664Nm) 440ci six-pack V8 became a popular option, offering similar real-world performance to the Hemi. These additions, as well as proper supply forecasts, increased sales to 82,109 in 1969, out-selling the mighty Pontiac GTO.

Motor Trend awarded the 1969 Road Runner its coveted Car of the Year title but, more importantly, it made Plymouth showrooms cool again. People flocked to dealers to see this new high-performance, low-cost muscle car. The fact that most buyers optioned all the equipment that had been taken out was just a bonus.

The Road Runner’s success and significance prompted Motor Trend to place it 12th on its recent ‘Top Muscle Cars’ list, and led Dodge to release its own version, the Super Bee – all thanks to a mischievous bird on Saturday morning telly.

GTX

In contrast to the bare-bones, trend-setting Road Runner, the flagship GTX was a more traditional muscle car – sitting at the top of Plymouth’s ‘mid-size 5’ line (GTX, Sport Satellite, Satellite, Road Runner, Belvedere).

Marketed as a ‘gentleman’s muscle car’, the GTX came standard with a 440 Super Commando V8 and Torque-Flite automatic transmission, with the 426 Hemi a US$546 option.

Introduced in 1967, the GTX received a comprehensive restyle in ’68, though sales suffered in the wake of the identically bodied, but faster and cheaper, Road Runner. This sales slide continued when Plymouth introduced a drop-top Road Runner in 1969.

The convertible GTX was dropped after ’69 and slow sales meant the end of the GTX nameplate as a stand-alone model in 1971.

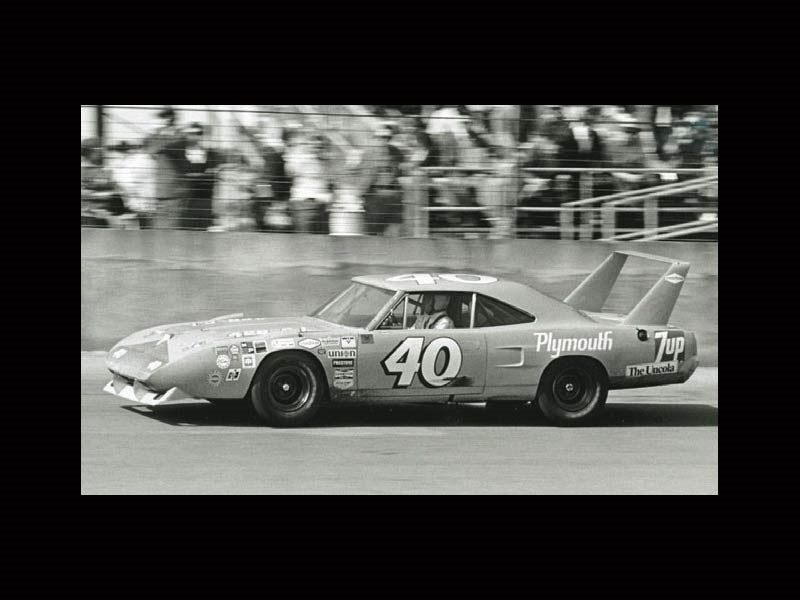

SUPERBIRD

The Road Runner formed the basis of the Plymouth Superbird, arguably the wildest looking muscle car ever built. Incorporating many of the lessons learned from its sister car, the Dodge Charger Daytona, the Superbird was developed specifically for the 1970 NASCAR season.

Powered by a competition version of the 426 Hemi, the Superbird could blast through the air at 200mph (322km/h), at least until NASCAR limited these ‘aero cars’ to 305ci engines for the 1971 season.

That wild bodykit added 19 inches to the Road Runner’s length, while the height of that towering rear wing, thought for many years to be a product of carefully calculated genius, was actually only that high to allow the boot to open.

Richard ‘The King’ Petty was the most famous Superbird driver, winning eight races in 1970. His electric blue racer was immortalised in the 2006 Pixar animated film Cars, voiced by Petty himself.

SPECIFICATIONS

1968 Plymouth Road Runner 426 Hemi

Engine: 6974cc V8, OHV, 16v

Power: 317kW @ 5000rpm

Torque: 664Nm @ 4000rpm

Weight: 1691kg

Gearbox: 4-speed manual

0-97Km/h: 5.3sec*

0-400m: 13.55sec*

Value: $80,000-plus

*Motor Trend magazine

*****

More reviews:

> Search more Plymouth reviews

Search used:

>> Search Plymouth cars for sale

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)