Mini Cooper 50 Years on

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

Mini Cooper

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

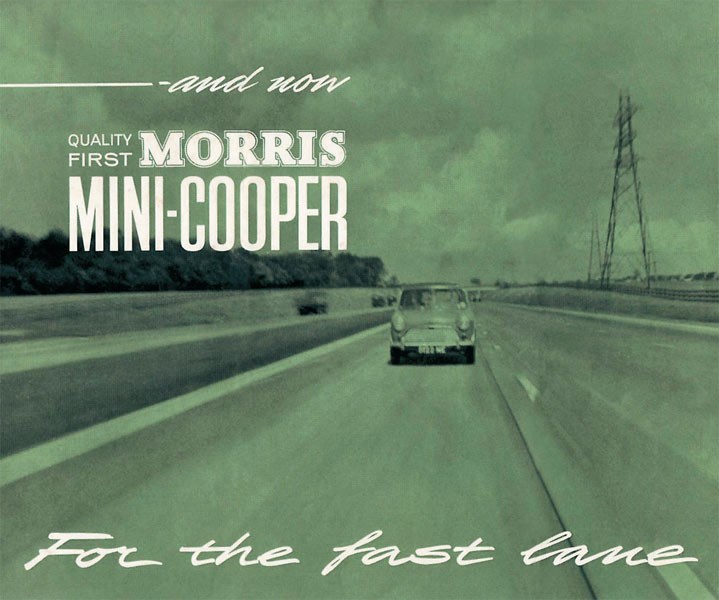

Already a global sensation, adding the name and engineering of a British F1 championship-winning team made the BMC 'Mini'

|

|

Mini Cooper

|

Mini Cooper

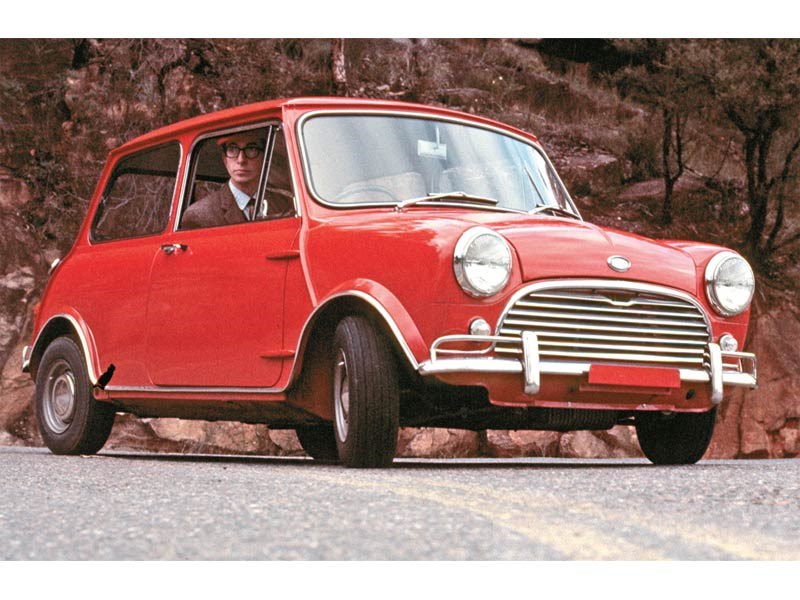

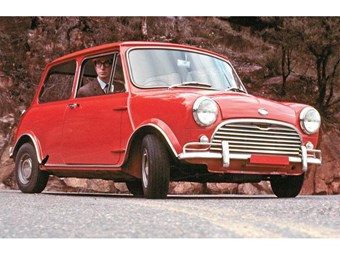

Nineteen sixty two was a massive year. In politics, the USA and Russia almost plunged the world into nuclear war over the Cuban Missile Crisis. On the sporting front, New Zealander Peter Snell broke Herb Elliott’s record for the mile run. Andy Warhol put on his first exhibition of "Pop Art", the first trans-Atlantic television broadcast was made via the Telstar satellite, and Marilyn Monroe was found dead in her apartment, aged just 36. It was into this environment that BMC Australia lobbed the completely left-field Mini Cooper.

Not only did the ‘flying brick’, as it became known, prove that the makers of the staid Austin A40 and Morris Minor had a sense of humour, it showed they were also serious about motorsport. The tiny, front-drive Morris 850 (Mini) had already been making its mark on Aussie roads and racetracks since its release the previous year. In fact, a locally-developed hot version of the Mini – the Morris Sports 850, featuring twin carburettors and an improved exhaust – was released as early as the end of August 1961. Peter Manton was one of the main people behind the car, which was sold through Manton Motors in Melbourne and P&R Williams in Sydney. Although a dealership-special model, the Sports earned tentative support from BMC and retained the factory warranty.

A month after the Sports 850, the UK suddenly found itself with an even hotter Mini – the Cooper. For anyone interested in motorsport, the name Cooper immediately meant racing, as John Cooper’s team had taken both the 1959 and 1960 F1 World Championships, with Aussie Jack Brabham in the cockpit on both occasions.

Cooper wasn’t the first to recognise the Mini’s potential on the racetrack, however. One of the first was Daniel Richmond from Downton Engineering, who raced an early Mini 850 with a fair bit of success in its class. But it was Cooper who had the ear of BMC, mainly thanks to using A-Series engines in his Formula Junior racecars of the time.

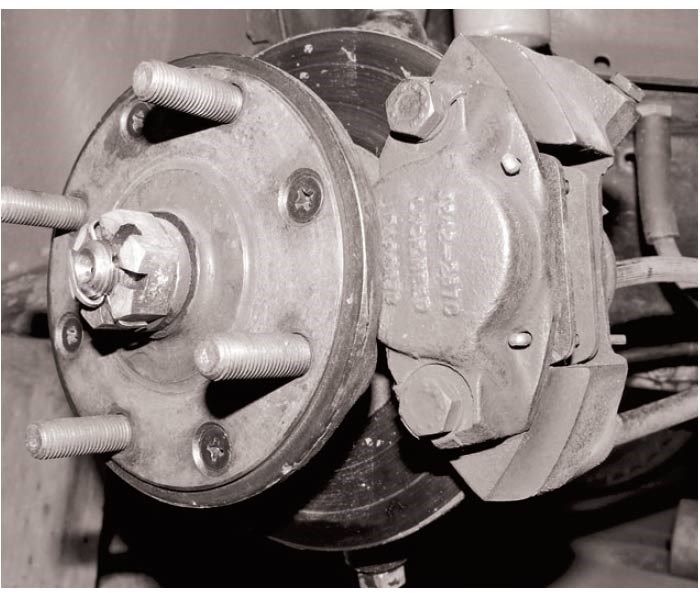

John Cooper’s top-of-the-tree status also stood him in a good bargaining position with the likes of Dunlop (tyres) and Lockheed (brakes), and he was friends with the Mini’s designer, Alec Issigonis – having competed against each other in their respective 500 specials after the War. Cooper was even loaned a pre-production Mini in early 1959 and drove it to Europe for a round of the F1 Championship. There, he loaned the car to Fiat/Ferrari engineer Aurelio Lampredi, who, after an extensive test drive, declared it "the car of the future". Folklore has it that after Cooper drove this early Mini, he said "let’s make one for the boys".

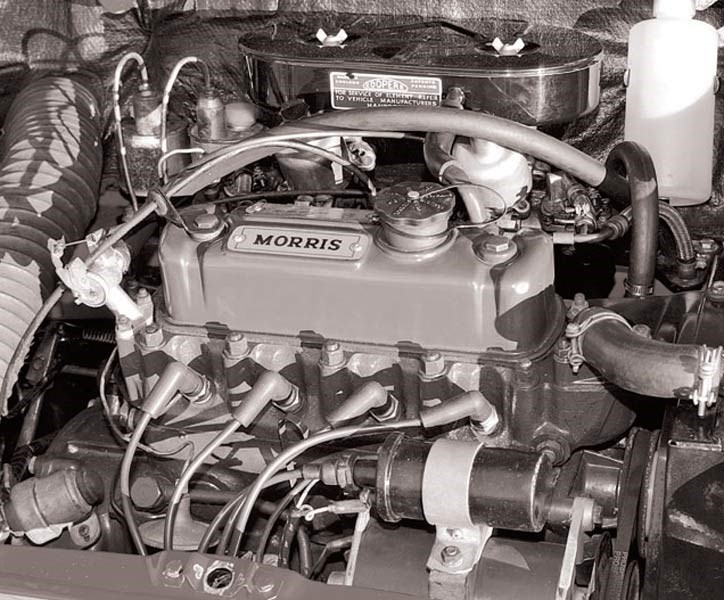

At the time, his three drivers – Brabham, McLaren and Roy Salvadori – apparently all had Minis for their personal transport. As is the case with most racing drivers, these cars were tinkered with using lessons learned from the Formula Junior engines. Cooper suggested to Issigonis that BMC could gain a fair bit of positive publicity by allying itself with his small, but well-reputed, racing business. He proposed a Cooper Mini, with 997cc Formula Junior-type engine, remote gear change and disc brakes. But it was racing where Cooper intended for the hot Mini to make its mark, in the under-one-litre class.

The Mini was, by design, extremely stable and handled brilliantly. Quite correctly, Issigonis always maintained that this was intended for safety, rather than for sporty performance. Despite his love of motorsport, he rejected Cooper’s idea, as it didn’t fit with his vision of what the Mini was all about.

Not to be deterred, Cooper demonstrated a Cooper-Mini to BMC Chairman George Harriman, who loved the idea and authorised the production of 1000 cars – the minimum required for motorsport homologation – although he was apparently sceptical that so many could be sold. John Cooper was to be paid a token £2 royalty per car.

Typical of BMC’s badge engineering policy, the Cooper was available in both Austin and Morris versions in the UK, even though both were built together at Austin’s plant in Longbridge. Although commonly

referred to as Cooper Minis or Mini Coopers, even in some brochures, the cars were only ever badged as Morris Cooper or Austin Cooper (with the Mk3 Cooper S of 1969 the only model ever officially badged Mini Cooper S).

Despite Harriman’s apparent scepticism on the popularity of a sporting Mini, a total of 24,860 997cc Coopers were built, of which 50 percent were exported, and a further 55,760 998cc Coopers (65 percent exported) by the time production ceased in 1969. On top of these figures were the various, giant-killing Cooper S versions.

The Cooper Mini was released in the UK only a month after the Sports 850 became available here, and BMC Australia was reported to be cautious about plans to import it, or assemble it locally. It would

take time to see if the Cooper version was substantially better than the twin-carb Sports 850, which, of course, it was.

BMC Australia may have been reluctant to take on an untried formula, but according to Modern Motor magazine in January 1963, another reason was that BMC’s Zetland factory was struggling to cope with the demand for the Morris 850, and introducing a second model to the production line so early would have been impossible. It was also felt by some people that the Cooper would be too expensive in Australia. But after early private imports showed how much better the Coopers were than the Sports 850, BMC Australia was soon assisting with a limited number of imports – at around £1100 according to

Sports Car World in February 1963.

With the on-going popularity of the Cooper in the UK and its emerging classconquering reputation, as well as the numerous calls for the car to be imported in greater numbers or assembled locally, BMC announced a local 997cc version (available only as a Morris Cooper) in November 1962. Despite any apparent misgivings or reluctance on BMC Australia’s part, the decision to release a local version must have been made early in UK production, as the first dozen CKD (Completely Knocked Down) kits were sent from Longbridge as early as March ’62.

At its release, the Aussie Cooper, with 997cc engine, remote gear change, disc brakes and twin carburettors, was £950. The Sports 850 was £790 at the time – just £37 dearer than the base 850 – but the

28 percent price increase for the Cooper was well justified by its improvements.

It was the first Australian-built saloon car to come standard with (tiny) disc brakes. While 52hp (39kW) may not sound a lot, with a kerb weight of around 600kg and the Mini’s superb handling, the Cooper was the sportiest saloon car on the market. Not surprisingly, it was also popular.

In order to easily differentiate the Cooper from the basic 850, it was offered with a contrasting roof colour – although some monotone cars, particularly black or white, were also built. The first 2000 or so were assembled from CKD kits imported from England, but from mid-1964, Aussie Coopers featured locally-pressed body panels, with the mechanical package of engine, transmission and brakes still fully imported from the UK.

In October 1962, just two weeks before the last Armstrong 500 at Phillip Island, the ARDC held a six-hour race for production cars at Bathurst. The Mini Cooper of Bruce McPhee/Barry Mulholland was the star of the show, easily winning its class, and giving notice for what was to come. But not enough cars had been built locally to qualify the Cooper for the Armstrong 500, so five Sports 850s were entered instead – finishing second, third, fifth, and sixth in class (based on price).

By the time the race had moved to Bathurst in ’63, the Cooper was wellestablished and 12 were entered to take on Mount Panorama. Doug Chivas/ Ken Wilkinson finished first-in-class in their Cooper, but more importantly, they managed sixth outright. Coopers also came in second, fifth, sixth, and seventh in class. The Mini’s giant-killing reputation was cemented.

Peter Manton owned one of the first Coopers assembled in Australia, which he campaigned with great success as part of the famous Neptune Racing Team until 1964, when he replaced it with an imported

1071cc Cooper S. By the time he sold it, the car held class records at most racetracks in Australia. In 1963, Peter finished fifth outright in the ATCC at Mallala in SA, which was a remarkable achievement for a 1.0-litre car.

The process of continually improving the Cooper began in November 1963, when the UK version went from 997cc to 998cc (with these new engines filtering through to Australian production around March/

April ’64). It may not sound like much of a change, but the 1cc difference was achieved by giving the engine a slightly larger bore and a shorter stroke, which allowed it to rev more freely without sacrificing torque. As with the 997cc, Australian cars were the low-compression version (8.3:1 compression as opposed to the UK’s 9.0:1).

A further change took place in September 1964, when an Australian-assembled 998cc engine with high compression was introduced. It is believed this was part of BMC’s plans to increase local content, in

order to meet government targets for tax incentives. These were the only Cooper engines of any type assembled in Australia.

Back at Bathurst in ’64, there were six Coopers entered, with Charlie Smith/ Bruce Maher finishing ninth outright and leading home a Cooper one-two-three class whitewash. Come September ’65, the 998cc

Cooper was discontinued in Australia after the release of the 1275cc Cooper S, but its motorsport career continued for a little while longer.

Although not greatly successful at Bathurst in 1965 – the new Cooper S stole the show, and almost the race, taking the first six places in class and third to ninth outright behind Ford’s Cortina GT500 – the regular Cooper continued to dominate its class on many racetracks around the country. By the time the renamed Gallaher 500 was held at Bathurst in October 1966, the 998cc Cooper was no longer considered competitive in most events. However, Peter Cray/Don Holland led home a thrilling one-two-three in Class B – behind the Cooper S’s first-to-ninth blitz in the outright standings.

While the Cooper made way for the Cooper S in Australia in 1965, it continued alongside the bigger-engined variants in the UK right up until 1969, when it was replaced with the Clubman-fronted 1275GT.

During its short 27-month assembly period in Australia, some 3887 Coopers were built. Of these, around 2800 were fitted with the 997cc engine, with the remainder having the 998cc – around half of which were the locally-assembled, high compression unit.

Such was the impact of the diminutive Cooper, and its bigger-engined brother, that these days most people don’t mention the name Mini without including the Cooper moniker. Almost anyone who’s ever owned a hot Mini will tell you they had a "Mini Cooper" and even BMW felt the name Mini was not worth having without the Cooper part attached.

Given its brilliance, who are we to argue?

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.png)