Lincoln Continental (1968-80) buyers guide

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

To make a big statement in a very 1970s kind of way park one of these Lincoln ‘Personal Cars’ in your driveway...

|

|

Buyers' guide: Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

|

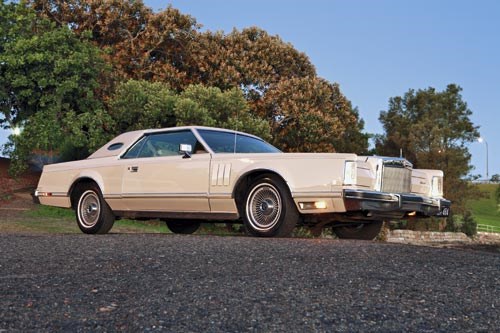

Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

‘Personal Car’ is the very American description for the genre of huge, luxurious and invariably inefficient coupes that appeared on US roads during the 1960s. Ford’s four-seat Thunderbird pioneered the fad in 1958 and was soon joined by Buick’s Riviera, the front-wheel driven Oldsmobile Toronado and Cadillac Eldorado.

Lincoln was slow to join the fray; however it could rightly claim a ‘PC’ lineage dating back to the 1930s. The first Lincoln Continental appeared in 1939, based on a coupe produced a year earlier for the ‘personal’ use of Edsel Ford. The name was revived in 1955 with the release of a Mark II version before being applied in 1961 across the Lincoln range.

April 1968 saw Lincoln return to the ‘personal car’ ranks with a Thunderbird-based Continental Mark III. Available only as a two-door coupe, the design mentored by Ford marketing guru Lee Iacocca incorporated a grille influenced by Rolls-Royce and spare-wheel ‘boot bulge’ with direct links to the original 1938 design. In a first for Lincoln, the Mark III’s headlights were concealed behind vacuum-operated covers.

Measuring almost 5.5 metres and with a 2970mm wheelbase, you’d imagine the Mark III would offer accommodation in keeping with its imperious dimensions. Not so. The split-bench front seat with power adjustment was broad and provided sufficient travel to almost touch the rear seat, so riding in the back was a cramped and claustrophobic experience.

Comforts included a timber veneer dash and door trimmings, power windows, map lights and a vanity mirror. The options list was headed by air-

conditioning and all bar a few hundred of the Continentals built in 1969 had it, while 84 percent came with vinyl roof covering.

Confirming Iacocca’s belief that Lincoln buyers were ready for a more stylish and sporty-looking model, 31,000 were sold during the Mark III’s first year – effectively doubling annual Lincoln sales.

The Mark IV model released for 1972 had a more bulky and angular shape that defined Continental styling for a decade.

This car was 100mm longer, with 76mm dedicated to extending the wheelbase and providing more interior space. The seductively curved rear wheel arches of the Mark III were enlarged, while redesigned ‘C’ pillars incorporated oval-shaped ‘Opera’ windows.

Although the 7.5-litre engine remained largely unchanged, its claimed power output – due to a regulation that stopped US car makers quoting ‘gross’ horsepower figures – was cut to 151kW.

Mark IV production peaked at almost 70,000 cars during 1973, defying the effects of fuel shortages and impact-absorbing bumpers that boosted weight by a further 70kg.

Various ‘special’ editions of the Mark IV and Mark V Continentals were produced, each with distinguishing colour schemes and variations to trim and equipment.

1976 saw four ‘Designer’ editions released – among them the silver-grey ‘Cartier’ and cream over metallic blue ‘Bill Blass’ versions. Dashboards in these Continentals carried a gold-plated plaque which could be engraved with the purchaser’s name.

The Mark V released in 1977 differed in detail only from earlier cars but weight was pruned by 127kg to a still-porcine 2115kg. The standard engine displaced 400 cubic inches (6.6-litres), with the ‘460’ optional until 1979. A higher final drive ratio improved economy but significantly blunted performance.

Despite mounting opposition to large cars, Americans loved and continued to buy Continentals. During 1979 when the ‘Bill Blass’ Continental at $16,000 cost $5000 more than a Town Car sedan, annual Mark V sales still topped 75,000.

ON THE ROAD

‘Lumbering’, ‘land-yacht’ and ‘overwhelming’ are adjectives that appear frequently and probably unfairly in magazine reviews of 1970s Continentals.

Writers whose preferred rides were Ferraris and Corvettes missed the point that people who bought megalithic Lincolns – and their General Motors-built rivals – really didn’t care about drag coefficients or mid-corner G forces. The Continental was designed to exude opulence and status – and succeeded on both counts.

All but the final Series V cars had Ford’s heavy and lazy ‘big block’ V8 with a C6 ‘Command Shift’ transmission. Heaving more than two tonnes away from a standing start presented no problems for an engine that produced almost 500Nm of torque at just 2200rpm and 0-60mph (0-96km/h) in a Mark III took less than nine seconds.

Personal experience some 20 years ago of a beleaguered Mark IV probably does today’s offerings some injustice. However, if you find one displaying similar behaviour, leave it alone.

That particular car produced alarming creaks and groans from the front suspension and would actually squeal its tyres in a straight line. Steering response was erratic and wheels would lock under minimal braking effort.

Much of the blame was due to a sub-standard right-hand drive conversion. Cars converted during the 1970s were subject to minimal regulation, allowing inexperienced or simply shoddy operators to work on these complex cars.

With all of its underpinnings aligned and working properly, ride will be pneumatic rather than jiggly and the steering wheel should move no more than 30mm before responding.

Brakes will always be a weak point on a car of this weight, so selecting a lower gear before attempting steep descents will minimize the need for frequent pumps on the pedal.

The standard Continental interior isn’t especially sumptuous, although the ‘Designer’ cars did incorporate some elegant touches. Leather trim was optional and of good quality, the seats on later cars had six-way adjustment and some came with a power sunroof. The headlights even switch on automatically via a dash-mounted sensor that detects when it gets dark.

By the late 1970s, even American luxury car buyers were unwilling to feed a 7.5-litre lump that would swallow 25 litres of fuel for every one hundred kilometres of city or suburban driving. The 6.6-litre motor that became compulsory in 1979 cut consumption by almost 15 percent. However, if you want to use the car regularly, seek out one with an LPG tank in its double bed-sized boot.

BUYER'S CHECKLIST

Body & Chassis

If you’re a competent welder with a few months to spare and a lot of sheet metal lying around, a rusty Lincoln might be viable. If not, check the sills, door bottoms and rear quarter panels, around the windows and the floor beside the front pillars. Any bubbling or discolouration of the roof covering is a good indication of problems beneath the vinyl. Cars that have recently arrived from the USA – and others that show signs of neglect – should undergo a hoist inspection to ensure they aren’t suffering serious structural rust. Good bumpers are difficult to find second-hand and expensive to repair. New indicator and tail-light lenses are available, but cost $110-150 each from US suppliers.

Engine & Transmission

The big, understressed V8s used in these cars need only basic maintenance to remain reliable for many years and more than 300,000 kilometres. Blue exhaust smoke indicates a tired but not necessarily dead engine. Leave the engine idling at the end of the test drive and listen for bubbling noises from a blocked radiator. Reconditioned replacement engines cost upwards of $3500. The hefty C6 automatic transmission is very durable, but be wary of jerky upshifts, slow engagement of reverse gear and serious oil leakage.

Suspension & Brakes

Excessive bouncing over minor bumps, creaking or hissing sounds when the steering wheel is turned and irregular tyre wear indicate worn suspension components or a dodgy/deteriorating RHD conversion. Cars that aren’t used frequently can suffer fluid leaks and other hydraulic brake problems, but new parts are available and not expensive – a kit of new brake drums, rotors, pads and hydraulic cylinders will cost around $1000.

Interior & Electrics

Allow plenty of time to check that all systems in the Continental cabin are ‘go’. Seats, windows, door locks, headlights and mirrors activate electrically and must be working properly for a car to justify top money. Even when in prime fettle, the air-conditioning is unlikely to perform like a 21st Century system, but should blow a solid volume of reasonably cool air. Worn leather or cloth will be expensive to replace and is more viably repaired by a trimmer who can match colours and patterns. Suppliers in the USA will provide complete replacement carpet sets for US$650, but shipping weight of 20kg will attract steep freight charges.

SPECIFICATIONS

Lincoln Continental (1968-80)

Number built: Mark III – 79,381;

Mark IV – 278,600; Mark V – 228,860

Body style: All-steel separate body/chassis two-door hardtop

Engines: 6.6 or 7.5-litre V8 with overhead valves and single downdraft carburettor

Power & Torque: 151kW @ 3800rpm, 482Nm @ 2200rpm (7.5-litre Mark IV)

Performance: 0-100km/h – 10.6 seconds, 0-400 metres – 17.4 seconds (7.5-litre Mark IV)

Suspension: Front – independent with coil springs, control arms, telescopic shock absorbers and anti-roll bar. Rear – live axle with coil springs, trailing links, hydraulic shock absorbers and transverse stabiliser

Brakes: disc front/drum rear with power assistance

Tyres: LR78/15 crossply or 235/75 H15 radial

Contact: Lincoln/Mercury Car Club of Victoria

Website: www.lincolnmercury.com.au

Unique Cars magazine Value Guides

Sell your car for free right here

Get your monthly fix of news, reviews and stories on the greatest cars and minds in the automotive world.

Subscribe

.jpg)

.png)